Juneau

Talus

Helping Forest Rangers Maximize Access & Conservation in America's Public Lands

Overview

TIME FRAME

Research - 10 weeks; Design - 10 weeks

TOOLKIT

Figma, InVision, InDesign, Principle

INDUSTRY ADVISOR

REI Co-op

MY ROLE

User research, prototyping, wireframing, UI design, usability testing, information architecture

TEAM

Tony Tran, Trevor Larsen

The Problem

Our nation's public lands are being loved to death. More people than ever are getting outside, but federal budgets to upkeep these lands keep decreasing.

How might we help forest rangers better fulfill their duties of balancing conservation and access in public lands?

Design Response

Talus helps forest rangers get out of the office and into the field, where they can do their most impactful work.

Actionable Data

Talus provides the most important information quickly, based on time, urgency and recency. It helps rangers see recent activities on trails and future planned activities to help with short-term planning.

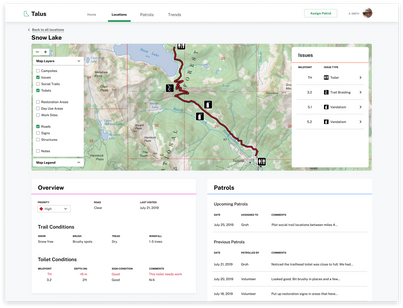

Trail Health, At a Glance

Looking over hundreds of thousands of acres of wilderness is no small task. Talus gives rangers a spatial view of their data, enabling them to better interpret and act on what they see, and reduce redundancy in which issues are reported.

Trail Reports 2.0

We've reimagined what trip reports look like —important and actionable data has been brought to the top, optimized for easy scanning. Longer term data and trends used for grant writing is sectioned off.

Research

Why Forest Rangers?

We started by looking at how we might we lower the barrier to entry for people interested in outdoor activities. But after five interviews with hikers and campers we quickly realized we were headed towards a dead end.

People's biggest constraints to getting outside were transportation and free time; two factors that, given our scope, we couldn't really design for. On top of that, we saw a pretty negative reaction to the idea of integrating technology with outdoor activity.

But nearly everyone spoke of our public lands as a special place; welcoming those of all abilities. Rangers mediate our experiences in public lands.

"I'm really invigorated by the National Parks story and the meaning of them to this country."

-Participant 1

A New Direction

We redrafted our research questions.

1) What role do rangers play in contributing to the goal of balancing conservation with access to protected lands?

2) How aware are visitors of their impact in parks?

3) What are the attitudes and behaviors toward technology in the outdoors; how is technology actually used outdoors?

4) What are visitors' expectations and aspirations for their outdoor experiences? How well are they met?

Recruitment

We primarily recruited through Reddit to get a variety of types of rangers both in role and geographic location, but also did in-person interviews at Mount Rainier National Park and Mount Baker -Snoqualmie National Forest. In our initial round of research, we were able to interview 12 rangers from various agencies and parks around the US.

A map of where our rangers came from.

While interviewing gave us a good view of what ranger's general job duties where, it was difficult to know what it was actually like there day-to-day, it being so different than any job any of us had held. To better understand what they saw each day, we went up to the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie Forest to do a contextual inquiry with Mac, a ranger at the Skykomish Station.

On a hike with a US Forest Ranger to learn more about what their day to day job duties look like.

Understanding HCI in the Outdoors

To get a more holistic view of what the technology + outdoor space looked like we went ahead with expert interviews, talking with two computer science professors whose expertise lay in HCI + Outdoors.

Besides gleaning insight into what sorts of constraints we would be working with in the design phase (durability, battery life, public attitude towards tech outdoors etc.) we also came away with several key takeaways that would help form our design principles.

"Human-computer interaction should never win out over human-nature interaction."

-Michael Jones, Professor of Computer Science

Brigham Young University

Synthesis

After looking through all of our research we affinity diagrammed all of our data from our 13 interviews.

From all of our data we derived four key insights that would guide us as we began our design phase.

Key Research Insights

1

As park visitation increases, rangers' interactions with the public have become more and more transactional.

3

Because front country trails are seen as safe, and providing catered experiences, visitors are lax on their planning.

2

People view visiting a national park through the same lens as any other vacation. However, parks are a government service, not a business that can meet market demands.

4

People will behave in accordance with their environmental values when they have the knowledge to do so.

Interested in learning more about our research phase? Access the full research report.

Design

We identified four potential design directions going forward and spent the summer ideating, prototyping, designing, and testing in the following opportunity spaces:

1) Provide contextual and actionable information to rangers and trail users.

2) Enable knowledge-sharing opportunities for visitors to support conservation-minded behavior.

3) Improve collection and sharing of visitor-usage data between rangers and land manager.

4) Leverage storytelling to help rangers advocate for their work and connect with the public and policy makers.

Ideation

We generated over 150 ideas from these four opportunity spaces and set out to downselect. Earlier in the research phase, we had generated design principles such as Support ranger agency to act on their first-hand knowledge. By looking at our ideas through the lens of these principles, we were able to quickly narrow down to less than 20. For example, a lot of our ideas involved restricting access, like a paywall feature for sensitive trail information that you could bypass through wilderness training. That violated our principle of: Design to maximize both conservation and access. We further narrowed by plotting our remaining ideas on an axis of feasibility and potential.

To help think through potential user journeys of our final six ideas, we storyboarded them. From here we could think through the what the most compelling use cases were, and also delve deeper into the technical constraints. We ended up combining two of the final storyboard concepts I sketched for our first prototype; trailhead check-ins for hikers and an analytics dashboard for rangers.

A trailhead check-in concept.

A ranger analytics dashboard concept.

Prototyping

Existing Solution

In our research, we found that a rangers already collected much of this information. It was just dispersed across various platforms, systems, and filing cabinets in a way that rendered the data useless.

V1

While we had thought through a lot of the technical constraints of our design, we still had a lot of unanswered questions around the desirability of what we were creating, and what exact information we should be focused on. We went out to test with hikers and rangers.

Hiker-facing app

Ranger analytics dashboard

We went to the Snoqualmie Ranger District to test our prototype out and discovered a few key findings that would alter our design path.

1) Data quality problems; the general public is just not really trained to know what is or is not an issue on the trail.

2) The district has a volunteer force of over 100 volunteers who come out regularly. These volunteers are trained and constitute a huge part of this district’s workforce.

3) This volunteer force needs to be assigned trails and managed, which means what we thought was a scheduling/workforce management issue of maybe 10 people was actually over 100.

We decided to focus more on the desktop analytics side, knowing that we could actually use high quality data that was already being collected by both rangers and their large volunteer force.

Understanding Rangers' Workflow

One thing we hadn't taken into enough consideration initially was how ranger's actually do their work with their current system. Creating a visualization of how their system works helped us see redundancies and helped us narrow in on what parts of the process we would design for.

Design Iterations

Over the next few weeks we made several trips up to both the Snoqualmie District Ranger Station and the Skykomish District Ranger Station to test with backcountry rangers as well as managerial rangers.

Homepage

The original homepage was giving rangers all the information they may need to know, but not necessarily taking their actual workflow into account i.e. information overload. We gradually moved towards a much simpler, time-based view.

"I just want a way to get to trail data quickly, and that's organized sensibly."

—Jamie, Wilderness Crew Lead, Snoqualmie District

Final design for homepage.

Trail Pages & Patrol Reports

We went back and forth (and back and forth) on what interaction paradigm to use for our patrol reports as well as how to display an individual trail's information. Each had their positives and negatives, and we found ourselves weighing ease/speed against readability, amongst other factors. We finally landed on the slide up modal interaction because it gave us the screen real estate to add a map (vital to decrease subjectivity of reports), and it had the flexibility to be invoked at any page of the system. The map ended up also being the main focus of the location page for this reason.

"One of our biggest problems is people submitting repeat issues, not realizing it has already been reported."

—Alex, Manager,

Snoqualmie District

Final design for the report modal.

Final design for the trail page.

Outcomes

Rangers get to spend more time outdoors, doing their most impactful work.

By using their resources more efficiently, rangers can meet their short-term (trail upkeep and public engagement) and long-term (funding, understanding of trail trends) goals, ensuring a sustainable future for public lands.

"This is way more approachable than layers and layers of spreadsheets"

—Jess, Wilderness Ranger,

Skykomish District

Design Spec

Reflection

Use real data

After testing our V1 at a ranger station, they were nice enough to give us read access to their entire spreadsheet they were currently using. Being forced to incorporate real data into our prototypes—messy, unclean, confusing, was challenging at times and threw our perfectly designed idea off kilter. But by the end, we had made a flexible system that would work not for a "perfect" user, but a real user.

Question Convention

With all of our great real data also came a lot of conversations about whether a data point or design was the way it was because it was effective...or because it had been put there years before and nobody had questioned it. Some of the data we had at first assumed was very important to a ranger's job (number of people on a trail or cars in a parking lot), due to its prominence in their existing system, turned out to be used by one ranger once a year to make grant proposals. If we hadn't asked probing questions during testing, they likely would have played an oversized role in our design response as well.